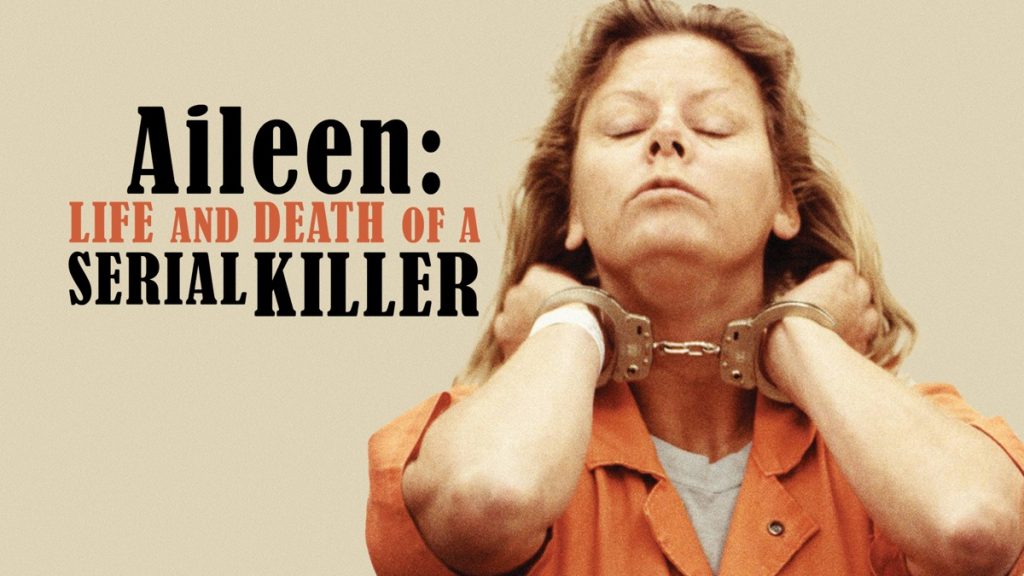

Pity Aileen Wuornos. She just never stood a chance. The daughter of a convicted child molester who hung himself in prison and a mother who abandoned her at six months, Aileen was raised mostly by her grandparents, Lauri and Britta Wuornos. By the age of nine, Aileen was prostituting herself to neighborhood boys, exchanging sexual favors for cigarettes. By age fourteen she was pregnant, though she gave the baby boy up for adoption upon his birth; that same year her grandmother, Britta, passed away, leaving Aileen and her brother in the sole custody of alcoholic Lauri. Shortly thereafter Aileen left home, living in the woods and depending on hitchhiking and prostitution as a means of surviving. Within the next few years, her brother Keith would die of throat cancer, Lauri would kill himself, and Aileen would take off for Florida—the state where she would eventually be apprehended for seven counts of murder, tried, and executed via lethal injection in 2002.

I am not implying that the circumstances of Aileen Wuornos’s childhood and the hardships she endured in her life provide a justification for the murders of seven men she committed in the ’80s. Neither is controversial documentary filmmaker Nick Broomfield (Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madame, Kurt and Courtney) in his newest film, Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer. Broomfield is, however, suggesting to us that there may be a connection from point A to point B to point C. After seeing his film, it is entirely too dismissive to suggest that Wuornos did what she did simply because she was “evil.”

Broomfield and co-director Joan Churchill shot this film as a follow-up to Broomfield’s Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer, which he made during her original Florida murder trial. Occasionally they cut in clips from the earlier doc, usually to underline a point about the lies that case’s participants have created for themselves over time—including Wuornos. At one point, both Broomfield and the earlier film are subpoenaed in the appeals process, as damning footage exists showing Wuornos’s original defense lawyer (hired off a TV commercial) smoking several joints prior to appearing in court, and making offers to sell her story to the highest bidder. In another heartbreaking sequence, modern-day interview footage with Wuornos—in which she claims to have lied about her story all along and that none of the murders were self-defense—is intercut with footage of her tearful recounting of the vicious rape and beating that led to the first shooting. It’s not entirely clear why Wuornos changes her story so drastically—it may be that she had been communicating with a born-again pen pal who suggested that she confess to her sins so that she might be with God, or that she had grown tired of waiting and simply wanted to be executed. Either way it is evident that Wuornos is lying, and Broomfield knows it.

By the end, Aileen has undergone yet another transformation. Though she is still unwilling to admit that the shooting of Richard Mallory—the first man killed—was self-defense (though she confesses that it was when she believes the cameras are not rolling), she has also retracted her position that all of the killings were in cold blood. She has become paranoid and posits several conspiracy theories, from claiming that the police were on to her but allowed her to continue killing for sensationalistic motives, to suggesting that she had undergone various kinds of subsonic torture in her prison cell. It is obvious that she is not mentally stable at this point, despite the fact that it takes all of 15 minutes for the court-appointed psychiatrists to determine her “mentally fit” for execution—a fact that Broomfield is quick to point out. Aileen tells the director that after 12 years on death row, she is ready to die—despite the visible fear in her eyes, we believe her. Anything this woman might have had to live for has been beaten out of her practically since birth.

Wuornos developed a relationship with Broomfield over their ten-year acquaintance—she liked him, and didn’t feel that he was attempting to exploit her the way so many others had. She likes the attention, too; she’s constantly aware of the camera, smiling and fixing her hair. This may be why she granted Broomfield her final interview, taped one day before her execution and included in the film. She’s completely detached herself at this point, and only wants to discuss her conspiracy theories about the police investigation. As she does, we see her grow more hostile; it’s not until Broomfield brings up Wuornos’s mother, however, that we observe the rage that has existed in her for so many years. These are the last images we see of Aileen Wuornos.

The film is at once fascinating and tragic; it simultaneously provides a compelling portrait of Wuornos and an indictment of the criminal justice system. Broomfield has more in common with, say, Michael Moore than with most other documentary filmmakers. He is an active participant in his film—appearing on camera, providing voiceover narration, and coloring the film with his personal feelings on the subject. He’s essentially telling Aileen’s side of the story, examining her past and interviewing those who knew her to compile a picture of what created the woman who murdered seven men. Though he never claims that Wuornos is innocent, it’s apparent that Broomfield does take issue with a system that seems almost doggedly determined to execute her.

Columbia TriStar is releasing Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer to coincide with their release of Patty Jenkins’ Monster, last year’s Academy Award-winning film based on Wuornos’s story. The shot-on-video image looks decent but not spectacular, and much of the archival footage is grainy and blurry. The two-channel audio presentation, provided with French subtitles only, is barely passable as well. The only extras provided are a few bonus trailers, including one for Monster. One doesn’t really notice that the disc is sparse or that the technical aspects haven’t really been souped up at all, though, because the footage contained within the film is so powerful. It speaks for itself.

Regardless of your personal feelings about Wuornos, I’m highly recommending this documentary. It’s probably best viewed as a companion piece to Monster, but I suggest watching that film first—allow yourself to absorb its emotional impact, then fill in the details with the factual information provided here.

For more movies visit Soap2day.