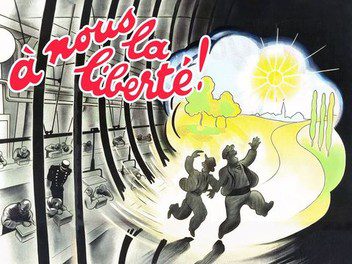

In this film, two fellow convicts attempt to escape from jail. Émile gets away while his friend Louis is caught and returned to prison. After some initial setbacks, Émile manages to build up a successful phonograph business. Louis is eventually released from prison and runs into Émile who gives him a job in one of his factories. Louis soon finds, however, that the factory is just like prison with its guards and assembly-line ways of making things and even eating meals. Émile’s plans to completely mechanize the whole operation combined with a blackmail scheme by several men who have recognized Emile for the escaped prisoner he is result in Émile and Louis combining forces, leading to apparent complete chaos at the factory.

Unlike its two predecessors, this film has two central protagonists the smooth Émile (played by Henri Marchand) who always seems to be hiding part of what he’s really thinking from us, and the easy-going Louis (a sad-faced Raymond Cordy who reminds me a lot of Harry Langdon). The two actors play off each other very well making me think that they might have been successful as a team had other films been made to capitalize on their chemistry. But it never happened, although both did appear in small roles in Clair’s 1952 film Les Belles de Nuit.

In À Nous la Liberté, René Clair again combines music and comedy, but this time adds a fairly obvious dose of social and political commentary to the mix. The disenchantment with the dehumanizing impacts of modern industry was obvious and a welcome comment from a film of this era. Clair’s stance, however, was weakened by his idyllic solution a utopia in which the workers are freed up by mechanization to idle their time away fishing or otherwise relaxing. More effective in hindsight is the film’s suggestion of a France oblivious to all going on around it, as portrayed by the sequence in which an aging French politician drones on to his audience about justice and liberty and patriotism, while the audience has long since lost interest preferring instead to concentrate on chasing money that has accidentally fallen out of a bag and is now blowing in the wind. By the late 1930s, France’s refusal to really pay attention to the machinations of an arming Germany would make the film prophetic in this respect.

Still for all its obvious commentary, the film works best when taken as a satirical piece that gently pokes fun at progress and at the rich, and essentially suggests that the meek shall inherit the earth. That’s never a bad direction to go, as Hollywood screwball comedies of the 1930s later found to the bottom-line health of their producers.

Criterion’s DVD of À Nous la Liberté falls roughly between Sous les Toits de Paris and Le Million in terms of image and sound quality. Once again, the image is full frame in accord with the original aspect ratio, with the transfer being created from a 35mm composite fine-grain master. It doesn’t look quite as crisp as Le Million and frequently seems somewhat washed out. Speckles and debris are more in evidence as well. On the other hand, at no time is there the degree of distortion in the image that is present on a couple of occasions in Sous les Toits de Paris.

The sound is another French Dolby Digital 1.0 mono track that has had audio restoration tools used to reduce pops, hiss, and crackle. While this has been effective to some extent, there is still an overall lack of presence that ranks it just below Le Million in this regard. English subtitles are provided.

The supplements on the disc comprise the best such package among the three Criterion René Clair DVDs. Two deleted scenes are included as is Entr’acte, a 20-minute surrealist short that Clair did in cooperation with French artists Francis Picabia and Erik Satie. Film historian David Robinson gives a lengthy audio essay on a plagiarism suit that the producers of À Nous la Liberté brought against Charlie Chaplin as a result of his film Modern Times. Nothing effectively came of the suit although there are obvious similarities between components of each film. Clair himself was not interested in supporting the suit, taking the position that if Chaplin was inspired by his film, then it was a tribute to Clair rather than a reason for legal action. The supplements are rounded out by a short 1998 video interview with Clair’s widow, Madame Bronja Clair.

For more movies visit Soap2day.