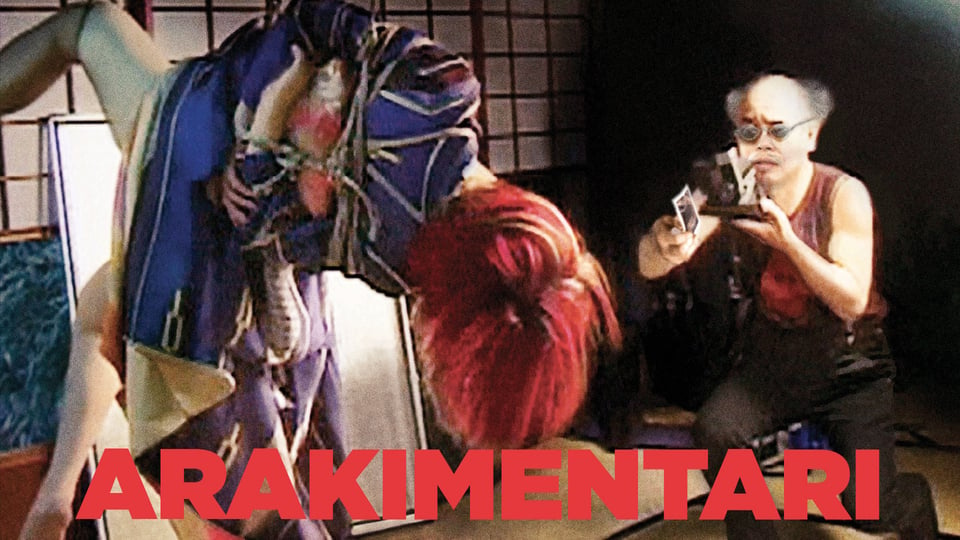

With more than 350 books published, Nobuyoshi Araki is one of Japan’s most popular photographers. But considering the overtly pornographic nature of most of his work, he’s also one the country’s most notorious photographers. Now, Tartan Video offers a look at the art and life of this controversial figure.

As a movie/DVD critic, I must attempt some degree of impartiality. If a filmmaker’s message or views do not gel with my own feelings, I must set that aside. Instead, I look at whether or not the filmmaker is successful in getting his or her point across, no matter whether or not I agree with it. And yet, there’s no way for me to start discussing Arakimentari other than revealing just how offensive the movie is.

Araki is not content just to capture nude women on film. Instead, it appears he is out to humiliate them. Depictions of the female form, both in Araki’s work and in this documentary, are extremely graphic, to the point where it stops being sexy and becomes very disturbing, if not downright disgusting. The interviewees here make several very good arguments for Araki’s work, explaining how it tears down the boundaries of censorship and conservative societal taboos, and that an artist should be free to express him or herself in any way. But after seeing Araki in action, he doesn’t seem interested in any of this. Instead, he makes raunchy comments about the women as they’re undressing in front of him, and he takes every opportunity he can to fondle their chests or put his hand between their legs. When flipping through some of his own photos at home, every time Araki comes across an image of a nude woman, he points to it and laughs loudly.

The short, bald, and paunchy Araki spends most of the movie wearing a white tank top with red suspenders, with small round sunglasses that hide his beady eyes. Perpetually red-faced and sweaty, the two remaining tufts of grey hair on the side of his head are always stringy and pointed, as if trying to escape from his brain. Yet despite his slovenly appearance, somehow Araki is always followed by lovely young ladies in kimonos and gangs of sharp-dressed yes men. I kept expecting Batman to come crashing through a skylight and haul him off to Arkham Asylum.

But then, about halfway through the film, we suddenly get a look at the work that made Araki famous. These photos are not pornographic, but are instead slice-of-life images of Araki’s wife, taken during and just after their honeymoon. Araki explains that his intent was tell the story of their love, portraying the emotion through simplistic pictures of her just doing the dishes, sitting on the patio, or sleeping peacefully. The photos then chronicle her untimely death, including heartbreaking black-and-white images of her in a hospital bed, and a close-up of their two hands holding each other, perhaps for the last time. For a while, the film becomes a tragic love story, ending with Araki’s photos of his wife’s cat wandering around their apartment, all alone. Then, there’s a scene showing the present-day Araki in a bar surrounded by his posse, asking a shy-looking young waitress whether or not she’s a virgin; he laughs in her face when she doesn’t immediately answer.

The filmmakers don’t hesitate to show off Araki’s work, even at its most pornographic. Like Araki himself, director Travis Klose doesn’t seem to care who he offends. There are extreme close-ups of, uh, female anatomy, as well as oddball images—nude women painted to look bloody, and photos doctored to show strange streams of light coming out of their bodies. Notable interviewees, including filmmaker Takeshi “Beat” Kitano (Dolls), fellow controversial photographer Richard Kern, and musician/singer/professional weirdo Bjork all heap praise onto Araki, going on about the groundbreaking nature of his art. Each of these interviews, however, is spliced together with footage of Araki giggling over his photos like an 11-year-old showing off a stolen Playboy to his buddies.

Shot on video, picture quality is sharp, with no evident flaws. The sound comes in DTS, Dolby 5.1, and Dolby 2.0 mixes, all in Japanese. There doesn’t appear to be much difference between the three, although the first two make the most of the occasional musical montage. The director’s commentary goes into detail about the low-budget day-to-day shooting of the movie. With an almost non-existent budget and a crew of only five people, it’s impressive the final project is as polished as it is. The “additional footage” is an extended interview with Araki, where he doesn’t appear to take the director’s questions very seriously, and instead indulges in more crass behavior. Also included are a photo gallery, the trailer, and trailers for other Tartan releases.

Photography is a mysterious art form. Like all artists, the photographer creates something out of nothing. But instead of a blank canvas, a block of clay, or even a bluescreen, the photographer is able to walk into a room and create a work of art from what’s there, just by framing it in a lens. It’s an “either you can do it or you can’t” skill. The best photographers can help us see the world in a new light just by taking the ordinary and making it exceptional. Does Araki truly have this skill, as museum displays and enormous book sales would seem to say, or is he just a dirty old man who happened to strike it big? It’s a question intentionally left unanswered and left up to the viewer to decide.

There’s a fascinating documentary hidden somewhere in Arakimentari, but it’s buried under the film’s onslaught of bad-taste porn and lewd behavior.

For more movies visit Soap2day.